— Review of Lu Nan’s Photography

They are hidden.

They are the forgotten people.

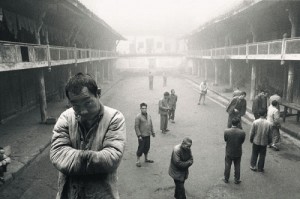

This photo is black and white, just like the others in Lu Nan’s album entitled The Forgotten People: The State of Chinese Psychiatric Wards. The grey color sets a grave tone. The light comes from the back, embracing most of the quadratic yard in the foreground. But it is not strong sunshine that brings hope, but rather the pale white that covers the plain playground. The building at the back is washed out. Those people in the brightness are barely visible. The light creates a misty atmosphere. You may even feel the fog moving forward, on the verge of engulfing t he people.

A dozen men are standing in the yard. All are adressed poorly. Some are wondering, some are just standing there, doing nothing. Several people on the right side of the picture are looking in the same direction, leaning. We are curious to know what is happening, but that i s beyond the border of the image.

However, there is something keeps your attention in the frame, because someone is staring at you. He is closer to you than the others, standing aloof from the crowd, wearing a dirty coat, with arms crossed. His head is lowered, and his face is dark with deeply shadowed furrows. He stands still, and he i hs looking at you, but there is ironic defiance in his eyes. You have nowhere to hide. You are forced to accept his examination. The longer you look at him, the more nervous you will get.

It is his eye that makes all the difference. Without that, the yard would be just as normal as the others. This principle applies to many other photos in the album. Under Lu’s lens, the people in the mental hospitals all over the country are playing cards, writing letters, taking shower, and having dinners, just like everyone else. It is not until you notice their eyes or facial expressions, which disclose their sorrow, despair, helplessness, absurdity, or indifference, that you suddenly realize that they are a bit different.

This man in the front of the picture is like a gatekeeper of the yard. He is staring at you, with certain iciness in his mockery, yet shows no intention of communicating at all. Even his lips are buried in darkness. His silence and protectiveness set a transparent wall, powerful enough to compel you step back.

We are not welcomed in this world.

As outsiders, “we” tend to observe, to interpret, and to feel privileged beyond what is shown in the pictures. While this photo is taken from a higher position that leads us to look down, the perspective emphasizes the outsider role. As normal healthy people, “we” tend to think they are poor, that they exist outside the mainstream, that they lack love, and that they need more care.

But even before we show our empathy, the strong composition of the photo turns the perspective around: this symmetrical shot with converging lines achieves the striking effect that the observers outside the picture are now being observed in their turn. What is in the photo becomes the centre of the world, and “we” are aliens now.

Looking through the album, it is easy to be shocked or touched. Most of the people in the pictures are silent and lonely. There is oppression and desperation under the grey photos, even though the images are self-constrained. They refrain from showing extreme pain or suffering.

The resolution between them and us is inevitable, but Lu successfully breaks through the wall and guides us into the world.

This album took Lu three years to complete, in the early 1990s. The work encompassed 38 psychiatric hospitals and over one hundred families. He interviewed his subjects, and spent time with them, before he ever raised his camera. He respected the patients, discussed with them before he took his shots, and wrote down the notes for each of the photo. His conscience and compassion are rooted in his images.

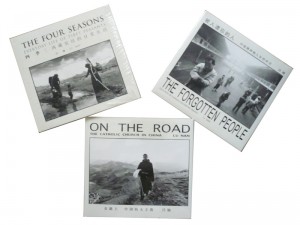

Lu creates documentaries like no other Chinese photographer. Besides psychiatric patients, he shoots Catholic believers in rural areas, Tibetan peasants, and prison camps in Myanmar. He deliberately gravitates toward underground or lost subjects. He has lived like a monk for the past 20 years, leading a simple and restrained life, away from the material world but close to his subjects. Even his closest friends can hardly find him. He himself is forgotten by the world – at least until the next striking album appears.

Edited by: Christian Caryl

我在香港的地铁、丁丁车、小巴、公交上断断续续的读完这本同样破碎的随笔集。太碎了以至于写评论也不知从何下手。

我在香港的地铁、丁丁车、小巴、公交上断断续续的读完这本同样破碎的随笔集。太碎了以至于写评论也不知从何下手。